Creating a New Chapter

No one ever grows up thinking their brand of something is particularly unusual. I knew my family wasn't the typical Jewish family since my Jewish dad and Christian mother raised us learning about both faiths. But that just made me feel like I knew more, not less. It never seemed odd to me to be the only Jewish kid in a classroom. It never struck me as strange that my extremely common Jewish last name was mispronounced Rah-zen, instead of Roe-zen. I didn't know that most synagogues don't have organs like the one in my synagogue, the oldest Reform synagogue in America, Charleston's Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim.

Every member of my family in Charleston was Jewish, and it never occurred to me there was any other way to be Jewish. My dad's grandparents had come through Ellis Island from Russia and Austria in the typical story of so many American Jews. But they made their way South, rather than staying in larger communities up north. That risk reaped rewards. My great-grandparents ran a grocery store in Charleston and within a single generation my grandfather became Charleston's first Jewish City Attorney. But as a result, I always saw my Jewish family as Charlestonians first. They were American, they loved Charleston and they were also Jewish. They socialized and lived among the other Jews in the city, but it wasn't the leading identity. We made latkes on Hannukah, ran around with all the other kids looking for the Affikomen on Passover, and ate matzoh ball soup on Rosh Hashanah. But at my Bat Mitzvah there was as much Southern food as Jewish. I never gave it a thought.

I didn't really appreciate the specificity of my Southern Jewish heritage, and its impact on my culinary identity, until I moved to New York and had an Israeli mother-in-law. She was the kind of cook who made her own gefilte fish from scratch and had multiple courses at every holiday meal. She was incredible. She gave me a whole new dimension to my Jewish identity. We had common ground being Jews who had grown up with different traditions than the vast majority of Jews residing in New York City. But with us, it was usually more about the food than the religion.

But then I got engaged to my now-husband. Weddings always have a way of showing us so much about ourselves, and this joining of two people - a Southern great-granddaughter of immigrants who left shtetls and a New York City-bred child of Israelis - certainly laid bare the cultural differences that exist even within such a small religion.

It started at our engagement party, thrown by my in-laws. My mother-in-law had made every morsel of food and beamed with pride. My 91 year old grandfather had flown up to New York and I saw him chatting in a corner to one of my husband's family friends of a similar age. She had grown up in Poland and survived Auschwitz to become a die-hard New Yorker. The bulk of their conversation centered on her surprise that he didn't speak any of his parents' mother tongues. No Russian, no Yiddish, and no later adoption of Hebrew. It had never struck me as odd that the ultimate Charlestonian had only spoken to his parents in a language they didn't learn until they were adults.

But the real reckoning came, as it always does, around food. My in-laws ate everything and certainly never kept kosher. But with something as religiously significant as a wedding, the context was apparently different. On a trip to Charleston to do some wedding planning we started to discuss options for the rehearsal dinner. I suggested a pig roast, without a single hint of irony or self awareness. My mother-in-law, respectful and kind to her very core, tried her best to gingerly explain to me why having a giant slab of pork in the middle of a Jewish wedding celebration might be a bit tone-deaf. Here we were, two Jews with exactly the same dietary habits in everyday life, but with a totally opposite sense of what a wedding looked like.

I have to give her credit for ultimately having the still-not-kosher shrimp and grits that I had also requested for the rehearsal dinner. And for also not saying a single word about the post-wedding oyster roast my dad's family threw in our honor. It was the first time in my life I had been struck by the interwoven texture of what it means to be a Jew in the South. Traditions melded with integration in a society where being Jewish wasn't necessarily the norm.

The truth is, there was very little Jewish culinary identity for most of my family before they came to the South because they had so little opportunity for it - it's part of why so many Jews came to the United States. In a taped interview my father did with his grandfather about his childhood, he mentions subsisting on mostly potatoes, herring and cabbage. He reminisced about an aunt in Moscow who once sent the family half a watermelon (the logistics of that are unfortunately lost to time!) as being among the highlights of his young life. And without access to greater resources, if a piece of cutlery touched meat and then dairy accidentally, they stuck it in the ground to 'make it kosher again'. His childhood was not one awash in special culinary traditions. We like to romanticize our cultural past, but in poverty there wasn't room to have much culture.

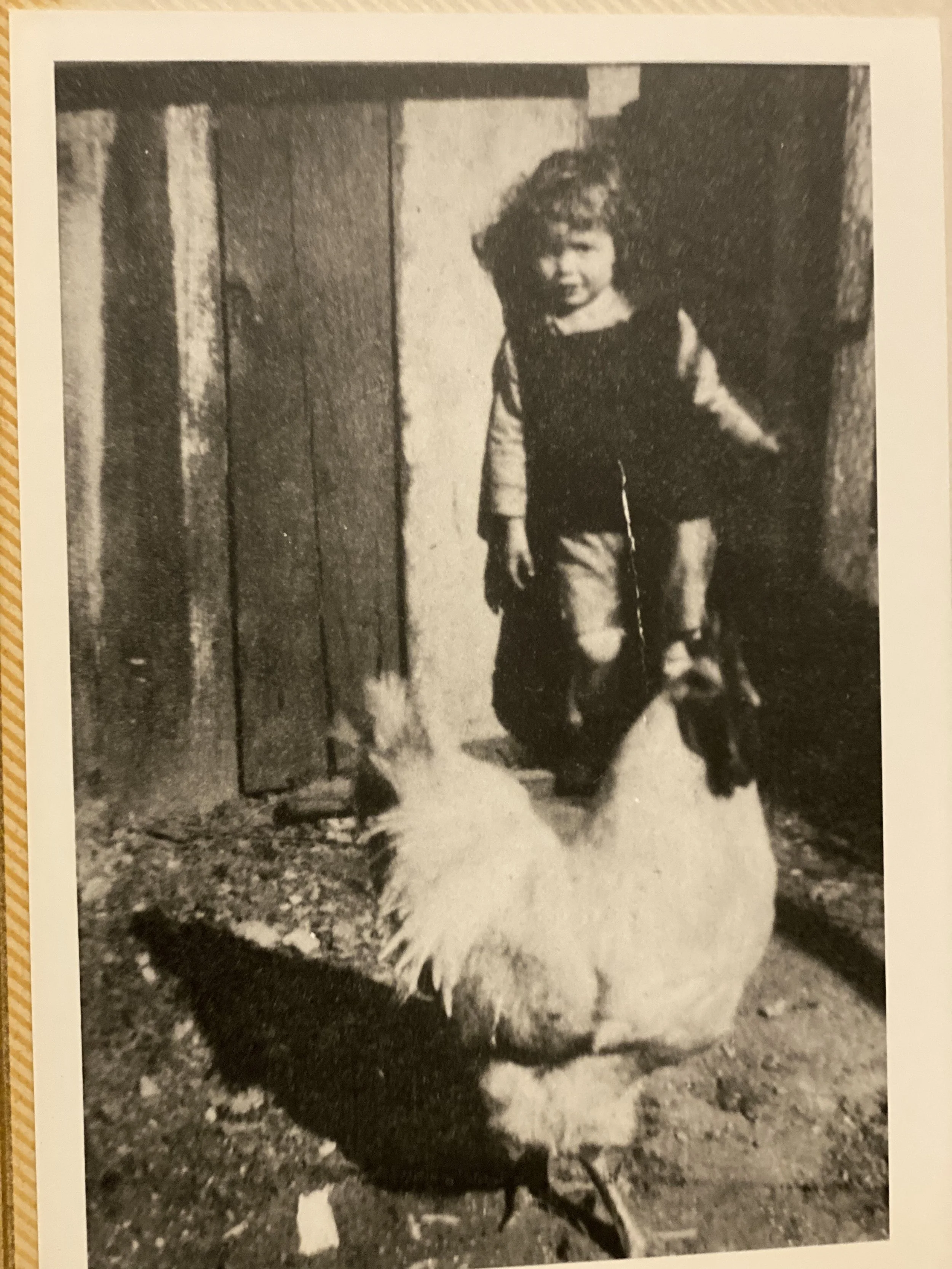

I think about what it must have been like for my great-grandparents. They raised their children in a Jewish community but discarded most of their language and food for a culture that, for them, lived up to the ideal of the American dream that propelled them to leave their homeland for a strange new world. My father grew up eating collards and grits along with his grandmother's matzoh ball soup. Charleston allowed them to keep their Jewish identity while growing interwoven roots into the society that had embraced them.

And generations later, in front of the Ashley river, beneath centuries-old oak trees on a warm October day, two Jews got married. Their Jewish families had both left Russia and Eastern Europe for a better life - but one family had found itself in Israel and the other in the South. We all come back together in the end, but the culinary traditions we find along the way can create a whole new chapter.

And of course… a Recipe!

Grits Casserole

I wanted to share this particular recipe because it feels quintessentially Southern but adds in the lox, which feels like the perfect nod to my Jewish life in New York. It also feels like family, since it's the kind of no-nonsense dish you could bring to family brunch or to a Seder.

Servings: 6-8

Ingredients

5 cups water

2 cups whole milk

1/2 cup salted butter, cut into 1-inch pieces, divided

2 cups stone-ground grits

1 teaspoon salt

8 ounces sharp Cheddar cheese, grated (2 cups)

16 ounces lox, cut into small pieces

3 large eggs, beaten

Preheat the oven to 350.

Bring the water, milk and half of the butter to a boil in a heavy pot on medium-high heat. Add the grits and stir continuously until the mixture returns to a boil. Reduce the heat, cover, and stir frequently for 10 to 15 minutes until the grits have thickened but are still a bit al dente to taste (your brand of grits really could make a difference here so always keep tasting as you cook in case it is less time).

When the grits are done, remove the pot from the heat, add the remaining butter, salt, and 1 1/2 cups of the cheese to the mixture until incorporated. Add the lox and eggs and then stir quickly and vigorously so the eggs don’t cook before being incorporated. Pour the mixture into a 13x9 or 8 inch baking dish and sprinkle the remaining cheese over the top. Bake in the oven for 45 minutes to 1 hour, or until the top is golden.